Defining any kind of literacy involving technology and information continues to be a challenge. The Oxford definition of literacy refers to “competence or knowledge in a specified area.” But what does this actually mean in a rapidly expanding digital world with new technologies including generative AI popping up all the time?

First, Digital Literacy

I remember trying to find a good definition of ‘digital literacy’ for my journal article on cultivating digital skills in arts and humanities programs back in 2016. I eventually settled on one from Allan Martin in the book Digital Literacies: Concepts, Policies and Practice about being able to “identify, access, manage, integrate, evaluate, analyze and synthesize digital resources, construct new knowledge, create media expressions, and communicate with others.” I also added a definition from Luciana Pangrazio in the journal Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education that combines technical skills with “an understanding of the role humans play in questioning, challenging and therefore shaping this techno-social system.”

But in some ways, these definitions were too broad to be useful except as a starting point. So I brought in research on the applications US students were using (e.g. word processors, spreadsheets) and their software skill levels or lack thereof. It turns out the whole ‘digital native’ thing was a myth — factors such as socioeconomic status, race, and gender were more important than age in terms of students’ tech skills and abilities. In my article, I provided examples of how teaching staff could build students’ digital skills through the curriculum they were already using. This was my attempt to make digital literacy more concrete in the context of my field, the arts and humanities.

Since then, my research and observations have confirmed how vague a concept digital literacy is, how difficult it is to know someone’s digital skill level, and how ill-equipped the industrial model of education is to handle the constant need for upskilling in technology. The OECD 2023 Digital Skills and Digital Inclusion report estimates that around 30% of Americans and 42% of Europeans lack basic digital skills, and this is contributing to a growing digital divide: the gap between those who can access and effectively use technology, and those who can’t. In New Zealand, a 2021 digital skills report shows 20% of adults lack essential digital skills such as the ability to upload documents, navigate cloud storage, or change privacy settings. The situation in other global regions is also concerning. This vast and changing area of technology eludes our ability to pin it down, standardize it, or ensure everyone is skilled enough.

Now, AI Literacy

Now add generative artificial intelligence, also known as generative AI, to the technology mix. When generative AI tools such as ChatGPT hit the public’s consciousness in late 2022 and 2023, the topic of AI literacy began emerging with more urgency. The term was previously used mainly in specialized computing contexts but is now being used more broadly as AI moves into the mainstream. For example, a recent special issue of the journal Computers and Education Open titled AI Literacy for All defines AI literacy as “a set of competencies that enables individuals to use and evaluate AI applications, and to communicate and collaborate effectively with them.”

Teachers, in particular, were some of the first to face the burden of how to upskill themselves and their students and deal with the ethical implications of generative AI. AI literacy is becoming an important topic in education, yet another thing to incorporate into the curriculum. But the fact is that everyone in society needs to become AI literate, not just those in school.

I saw an opportunity to provide a structure to help guide AI skill-building both in and out of educational institutions. I wanted something more concrete than the usual definitions, something to use and build on. I knew people were wondering: Where do we start? What skills do we need now and in the near future relating to AI, especially generative AI?

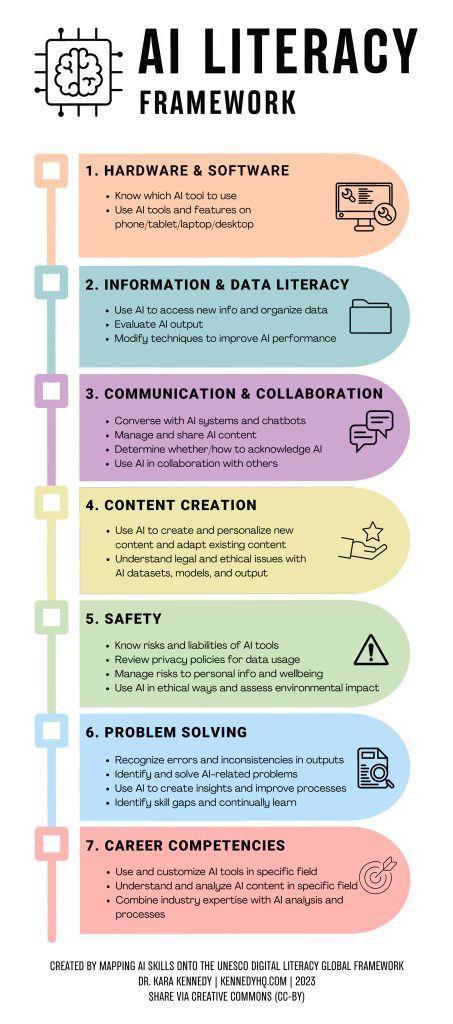

So, using UNESCO’s 7-point Digital Literacy Global Framework as a guide, I mapped AI skills onto it to create the AI Literacy Framework. I first presented the framework at a cultural heritage conference in November 2023 (see the recording on YouTube of my talk From Artifacts to Algorithms: Fostering AI Literacy).

The framework is available as a JPG or PDF file and shareable via Creative Commons. I know the AI tools will continue to change, but there are some core principles we can use when we look to cultivate AI literacy among ourselves and our communities. The response and engagement with my framework has been fantastic so far, and I plan to keep iterating on it and curating other resources that are useful in the AI literacy space. Let’s not let the digital divide become the AI divide!